Over the course of drafting a management plan for Madron well and chapel area, and in order to inform it, we commissioned an archaeological desk based assessment, a habitat walkover survey of the wider wetland area (of which more next blog), and an archaeological survey drawing of the wider well moor area including chapel and well structures. Over the course of 2022 we have been adding vastly to our understanding of these two charming and important Medieval structures and the wider landscape that linked them.

Over the course of drafting a management plan for Madron well and chapel area, and in order to inform it, we commissioned an archaeological desk based assessment, a habitat walkover survey of the wider wetland area (of which more next blog), and an archaeological survey drawing of the wider well moor area including chapel and well structures. Over the course of 2022 we have been adding vastly to our understanding of these two charming and important Medieval structures and the wider landscape that linked them.

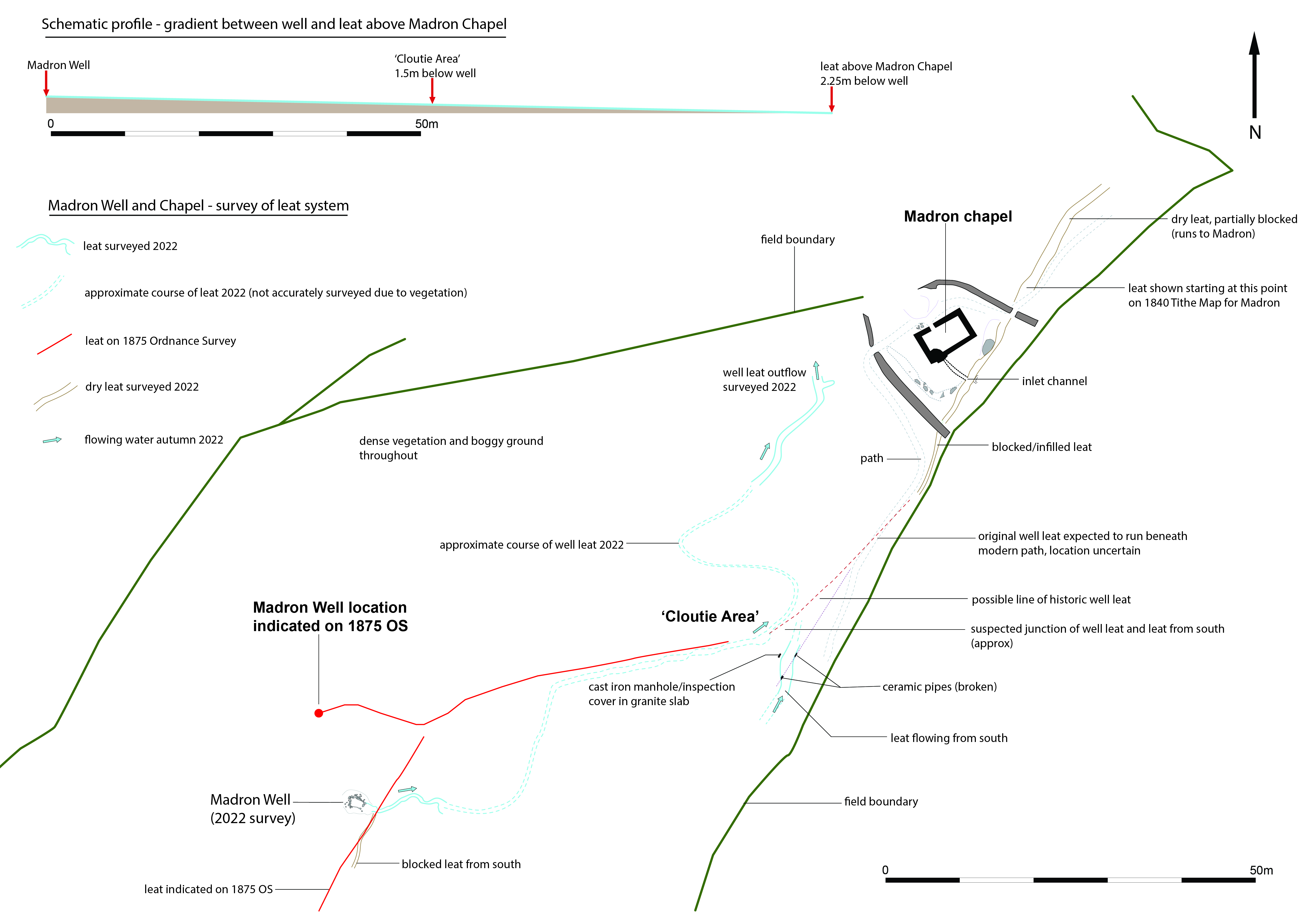

We know that the chapel and well are linked by a water channel or leat, quite possibly a modified stream that runs inside the wet wood that now fills the area of ‘Well Moor’. The moor itself, now a wet and atmospheric woodland habitat, was until the early 20th century a seasonally wet but open grassland used for grazing - see image right of the Well in 1900, surrounded by grass. The leat that links the chapel and well snakes about and follows the contour of the hill so exactly that despite the chapel appearing to be slightly upslope of the well, it is ever so slightly below, to the tune of about 2.25m. Historical records make note of the improbable seeming water flow from the well to the chapel and beyond to Madron parish church which looks to move uphill. Astonishingly, remnants of an earth banked leat do still survive in the wet woods, although now heavily obscured by muck, mire and trees; a feature of this complex that has not been formally recorded before. The leat running on from the chapel towards Madron can be seen clearly today and was noted in 1654 as already being a feature of the landscape taking water to Madron then later, onwards to Penzance.

Historically the first formal records and structures on the site of well and chapel appear in the early Post Medieval period; although as a strongly flowing water source in the area there is a high probability that it was known of and used in Prehistory, there being many sites and routeways dating back before then in the vicinity. The May time focus of the historically noted visits to the well may also be seen to hark back to pre-Christian Beltane celebrations which suggest earlier origins as well.

Historically the first formal records and structures on the site of well and chapel appear in the early Post Medieval period; although as a strongly flowing water source in the area there is a high probability that it was known of and used in Prehistory, there being many sites and routeways dating back before then in the vicinity. The May time focus of the historically noted visits to the well may also be seen to hark back to pre-Christian Beltane celebrations which suggest earlier origins as well.

The well was noted in c. 1590 by one John Norden as having long been famed for ‘the supposed virtues of healing which St Maderne had theirinto infused’ (more on the folklore surrounding the well in 2023). In 1654 the chapel was noted as being roofless but still having a hawthorn or thorn tree of over a foot in diameter next to it. Both these things suggest the chapel and well were there for quite some time before 1590, possibly as a part of the wider Medieval estate of Landithy, which was not only connected to the chapel and well by leat but was originally run as a preceptory within the Medieval period. In any case it seems the well and chapel building existed at the same time as part of a wider network of water management and religious focus. Considering the now only seasonal flow of water into the chapel building, but the strong water issuing forth from the well head itself all year round, one has to wonder whether that was always the case; hence the two contemporary sites ensuring a water supply all year round between them. Alternatively the small structure around the well may just formalise the shape of the spring in order to direct water better into the leat taking water to the chapel and beyond. Either way it is a long standing strong water line for Madron Churchown so must always have been a decent amount of water.

Current land use and more intensive farming in the area now means the level of water in the well and therefore chapel and leat is much more seasonally variable. The well moor area is now subject to a huge amount of seasonal water runoff from the surrounding fields, something that would not have been happening so markedly before the mid-20th century. So, whilst the area would have looked very different when the chapel and well were built, it still would have been a landscape with a focus on water management and land use that worked more sympathetically with that. The remnants of this system can still just about be seen today but changing land practice, including the cessation of grazing on well moor and increased seasonal rainfall paired with a lack of maintenance of these old water lines as more modern water sources became used now means we have a wet and boggy woodland - see image right of the Well in 2018.

Current land use and more intensive farming in the area now means the level of water in the well and therefore chapel and leat is much more seasonally variable. The well moor area is now subject to a huge amount of seasonal water runoff from the surrounding fields, something that would not have been happening so markedly before the mid-20th century. So, whilst the area would have looked very different when the chapel and well were built, it still would have been a landscape with a focus on water management and land use that worked more sympathetically with that. The remnants of this system can still just about be seen today but changing land practice, including the cessation of grazing on well moor and increased seasonal rainfall paired with a lack of maintenance of these old water lines as more modern water sources became used now means we have a wet and boggy woodland - see image right of the Well in 2018.

The sites are not lost though and small annual maintenance works should help to keep them accessible.

Above - drawing of Madron Chapel enclosure