West Penwith is classed as an historic landscape; a lot of it a living, working landscape with large parts of it not changing much in thousands of years. So much of what you look at today, mostly without realizing, is actually prehistoric or adapted prehistoric boundaries and fields. People say there is a ‘feeling’ to the place – that’s probably a lot to do with it, it just feels old! Farmers have been working the land in much the same way from the Bronze Age through to the present day, although there are monuments from the earlier Neolithic period as well, providing the odd megalithic mystery to contemplate (usually with a view). And whilst the light tread of the Mesolithic inhabitant is invisible, it is there, in the odd flint scatter and fire pit, found by chance, reminding us that folks have been roaming around here for 10,000 years or more.

West Penwith is classed as an historic landscape; a lot of it a living, working landscape with large parts of it not changing much in thousands of years. So much of what you look at today, mostly without realizing, is actually prehistoric or adapted prehistoric boundaries and fields. People say there is a ‘feeling’ to the place – that’s probably a lot to do with it, it just feels old! Farmers have been working the land in much the same way from the Bronze Age through to the present day, although there are monuments from the earlier Neolithic period as well, providing the odd megalithic mystery to contemplate (usually with a view). And whilst the light tread of the Mesolithic inhabitant is invisible, it is there, in the odd flint scatter and fire pit, found by chance, reminding us that folks have been roaming around here for 10,000 years or more.

Many of the sites and monuments still visible today have been adapted and altered many times over the years so it’s often hard to imagine what they might have looked like at any one time, let alone when they were in use. The remote locations and enigmatic appearances of some of these sites also confuses they eye. And often, so little remains to look at on the ground that only a trained eye can make out what is there. The vigorous vegetation that we know and love and love to scythe also doesn’t help.

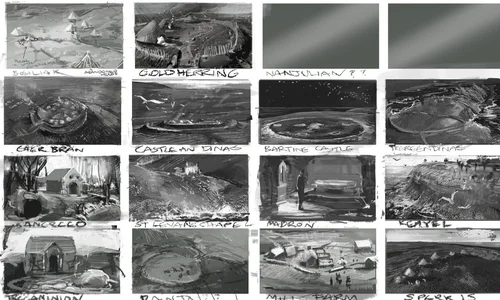

With that in mind, we engaged artist Phoebe Herring, who specializes in historic reconstructions, to produce a series of reconstruction drawings of 14 sites that the PLP is working on. Based on archaeological evidence they present a tantalizing glimpse of what life might have been like in some of these sites.

One of my favourite works so far is the drawing for Bartine castle cairn enclosure at the top of the page – midnight on the autumnal equinox for the year 2000 BCE (Bronze Age), see also this time regressed star map with stars named! Quite different to today's night sky, not least of all because it would have been a totally dark sky back then, something I hadn’t really thought about, so the stars appear much brighter.

One of my favourite works so far is the drawing for Bartine castle cairn enclosure at the top of the page – midnight on the autumnal equinox for the year 2000 BCE (Bronze Age), see also this time regressed star map with stars named! Quite different to today's night sky, not least of all because it would have been a totally dark sky back then, something I hadn’t really thought about, so the stars appear much brighter.

Six of Phoebe Herring's stunning recreations are now available to view on our website here, with more to be added in the future. Phoebe has very kindly shared with us her process for creating these pieces of art below.

"Before beginning the images, I created thumbnails to ensure that the paintings weren’t compositionally confusing or repetitive, and that there was a flow between the paintings if they were displayed next to each other. I find this is always a good idea when planning sequence of images, but it was especially important here given the danger that the many hillforts and chapels might become monotonous. I needed to ensure that each of these felt exciting and distinctive.

"This meant moving the viewpoint around and thinking about using weather and time of day to drive visual interest and distinctiveness. I wasn’t doing heavy historical reference at this stage, being mostly driven by aesthetics. It’s easy to tweak details at the end of the process but very difficult to change base composition, so it’s really important to get the angles right from the start.

"This meant moving the viewpoint around and thinking about using weather and time of day to drive visual interest and distinctiveness. I wasn’t doing heavy historical reference at this stage, being mostly driven by aesthetics. It’s easy to tweak details at the end of the process but very difficult to change base composition, so it’s really important to get the angles right from the start.

"All of the paintings were done in Photoshop, using a graphics tablet.

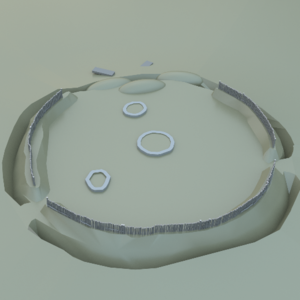

"Once these were signed off, it was time to tackle the individual images. I started this process with the archaeological site plans. I use these to create 3D digital maquettes which I then referenced to create an accurate scene. I lit the maquettes to provide a reference base. For some sites, like Gurnard’s Head and Castle an Dinas, I skipped this stage because the dramatic surrounding landscape would have taken longer to model in 3D than to paint in 2D.

"But the maquettes were very important for lots of the images as they  helped me avoid archaeological inaccuracies at the start of the process and gave me complete control of my camera. That said, I still prefer to decide on base compositional angles at the thumbnailing stage than in 3D – there’s a danger that all that camera freedom results in gimmick angles.

helped me avoid archaeological inaccuracies at the start of the process and gave me complete control of my camera. That said, I still prefer to decide on base compositional angles at the thumbnailing stage than in 3D – there’s a danger that all that camera freedom results in gimmick angles.

"With the maquette or sketch ready, I would then return to Photoshop and begin to paint the scene. I keep relevant images on my other monitor – often opening Google Earth to get a feel for the lie of the surrounding terrain and scrolling through ground-level site photos to reference the present-day ground cover and scale.

"Weather conditions and atmosphere were decided on back at the thumbnailing stage, but I often like to expand on them by adding a sense of the prevailing wind and by strategically placing reflections. This is also the stage where I add human figures. I’d previously decided on the theme idea of the hillfort being under construction, but this stage is where I explore what that actually means in terms of character action.

"Additionally, this is where I ask fellow artists and also archaeologists for feedback on the piece. I’ll sometimes find that I’ve misread a site map or made a mistake with the details. I’m especially grateful to Pete Herring for honest insightful critique and access to many great photos of West Penwith.

"The final stage is just to spend plenty of time adding all the little details that will hopefully make the scene feel real. I like to add clutter and mess to the scene to make the past feel lived in. At this stage, I’ll research photos of historical re-enactments but also look at present-day wooden structures, outdoor enclosures and street markets to steer my thoughts on how people might have used the sites."

"The final stage is just to spend plenty of time adding all the little details that will hopefully make the scene feel real. I like to add clutter and mess to the scene to make the past feel lived in. At this stage, I’ll research photos of historical re-enactments but also look at present-day wooden structures, outdoor enclosures and street markets to steer my thoughts on how people might have used the sites."

On the right you can see the original maquette for the reconstruction of Caer Bran hillfort, and the final illustration once Phoebe has added all her final artistic touches.